Obstacles abound in the path to ethanol’s future prospects: Getting its carbon intensity properly measured, getting that intensity down, addressing criticisms.

A major hurdle to ethanol-to-jet fuel was cleared just before Christmas when the U.S. Treasury Department announced that an “updated GREET” can be used to determine lifecycle emissions for the sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) tax credits authorized in the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

“Treasury made the right call to enable the use of GREET to determine the carbon intensity of SAF,” says ACE CEO Brian Jennings. “GREET is the global gold standard for calculating GHGs from transportation fuels and the most up-to-date, accurate model reflecting the best-available science, including farm practices.”

Jennings applauded the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s leadership “to help fortify the GREET model to satisfy any questions about whether it is a similar methodology to the CORSIA model. Allowing the use of GREET for the 40B SAF credit is consistent with the statutory requirement for Treasury to use GREET for the 45V Clean Hydrogen credit and 45Z Clean Fuel Production credit.” CORSIA’s default value finds U.S. corn ethanol’s carbon intensity (CI) essentially equal to petroleum-based jet fuel.

The Department of Energy (DOE) sees biofuel as absolutely essential for decarbonizing aviation fuel says Valerie Reed, director of the Bioenergy Technologies Office in DOE’s Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy. “Existing industry already has a lot of capital in the ground, so we can produce alcohol-to-jet fuels quicker and at a lower cost than some of the more advanced technologies that we’re going to need to move into in the future.”

The initial three-fold increase in U.S. SAF production, from 5 million gallons per year (MMgy) to 16 MMgy, has been supplied by fats, oils and greases converted with HEFA (hydroprocessed esters and fatty acids) — a process similar to petroleum refining. But HEFA’s ability to meet the current U.S. 17.5-billion-gallon aviation fuel market will be limited, Reed points out. Feedstock prices have surged due to tight supplies, plus the demand for renewable diesel (RD) by other sectors needing to decarbonize, such as trucking, marine and rail, may incent a shift towards RD over jet.

SAF sets up a really good opportunity for ethanol to be the next generation of aviation fuel, Reed says, “and continues to provide for ethanol producers and corn farmers as well as moving into cellulosic.” The current 17-billion-gallon ethanol capacity already serves a purpose, so supplying aviation demand can potentially provide market pull for cellulosic ethanol. “We have learned from the failures of the past,” she says, with much of the current research aimed at solving remaining engineering challenges, such as handling and preprocessing cellulosic feedstocks.

The IRA incentives address cellulosic’s other challenge — cost. The incentive starts at $1.25 per gallon for SAF meeting the CI reduction threshold and an extra penny for every point better than that up to $1.75.

Lowering CI

“The challenge to the ethanol industry is ensuring the carbon intensity fits within the definition of sustainable aviation fuel that is 50 percent less than jet fuel,” Reed says.

And a challenge it will be. The energy expended to make SAF adds about 30 CI points, which is roughly equal to what an ethanol plant would be able to slash from its CI if it sequesters its CO2. But only a handful of plants in North Dakota and central Illinois are situated above suitable geological formations, and the future of proposed pipeline projects is uncertain.

“If you can’t sequester, what is your plan to decarbonize?” asks Neal Jakel, president of Fluid Quip Technologies. An ethanol plant’s CI score is impacted by about 25 points on energy inputs. “We’ve been doing energy studies — where is a plant losing energy, where is its energy going today? We put together a list of projects and opportunities.” There are ways to capture an easy point or two, he says, while evaluating bigger ticket items that can really move the needle. For some, the first thing to focus on is yield optimization — spreading energy inputs across more gallons brings down the CI score. Another consideration, Jakel adds, is to make sure one project doesn’t cannibalize a better one down the road.

Only a dozen or two plants approach a CI score that puts them in striking distance of meeting SAF’s needs, assuming the revised GREET is going to account for farm-level CI reductions or CCS becomes a reality. Thus, most plants won’t be able to capitalize on the near-term SAF incentives, although Jakel says, “the real demand is going to be SAF long term.” The entire industry, however, is shifting focus to decarbonization. Low carbon fuel standard markets are moving beyond the West Coast to all of Canada plus multiple state legislatures are considering their own versions. In 2025, the technology-neutral 45Z Clean Fuels Production Credit will give an incentive to all fuels meeting the threshold CI reduction, valued at two cents per gallon per point of CI reduction below the threshold, says Jakel, with aviation fuels getting a higher incentive.

Ethanol producers will have to evaluate what diversification strategies they want to pursue and what technologies make the most sense, Jakel says. There are multiple approaches, but the big change is that technologies that didn’t pencil out with relatively low natural gas prices could now pay off from CI reduction.

Addressing Criticisms About Ethanol’s Image

While treasury’s announcement to use GREET for SAF is good news and the ethanol industry has multiple ways to decarbonize, it still faces an image problem. Another announcement a couple of weeks earlier illustrated the challenge: Virgin Airline’s news release on its 100 percent SAF flight from London to New York reported the fuel was 88 percent HEFA and 12 percent synthetic aromatic kerosene “made from plant sugars, with the remainder of plant proteins, oil and fibres continuing into the food chain.” It took some digging into more industry-oriented media to confirm it was ethanol — the fuel that cannot be named.

Overcoming that image has been a major goal for Gevo — a company with ambitious plans to achieve net zero ethanol and SAF. The company has upwards of 400 million gallons signed up for in offtake agreements with airlines, says Lindsay Fitzgerald, vice president for government relations, “but we still have to get this facility built.” Key to that is building a base of supporters and policy advocates. “What everyone in this space needs to see is that we have long-term, consistent policy to support what we are doing,” she explains.

To accomplish that, Gevo has been bringing customers and their corporate customers out to Luverne, Minnesota, to tour Gevo’s plant and a nearby farm. “It’s been a game changer,” Fitzgerald says. Most visitors don’t know that converting corn to ethanol produces an equal amount of feed and oil. And more than 75 percent never set foot on a farm. “A lot of people come just not understanding. Almost everybody leaves neutral and a handful leave changed to the bottom of their soul — it’s amazing to see it happen.”

Luverne farmer Shawn Feikema hosted close to 150 people in the past year. “I’ve been explaining to others who aren’t in agriculture why corn can be part of the SAF solution.” That’s included people from Boeing, Airbus, Pratt and Whitney, Nike, Google and Bill Gates Foundation. “They are a sponge for knowledge,” he says, “They don’t have the opportunity to talk to a farmer and I’m just telling them what we do. That story sells itself.”

The Feikemas are the third generation now managing a diversified farm raising around 7,000 acres of crops and finishing 2,000 calves. “My brother does all the cattle stuff and I do the cropping and business side. My wife does bookkeeping and my brother’s wife does the livestock records.”

While corn and soybeans are the primary crops, the Feikemas grow 200-300 acres of alfalfa and grass for the livestock and another 700 acres of various small grains such as rye, oats or triticale. The small grains provide straw for the cattle, break weed pressure and spread the workload for the family and their seven full-time employees. Manure, cover crops, no till and ridge till all play a part in the Feikema farming practices.

The visitors are open minded, Feikema says, and very interested in their farming practices. “The biggest thing is technology. They have no idea of the level of technology, or of education and the things we manage,” he says, citing precision ag techniques that support variable rate fertilizer and seeding, plus cloud-based data collection that records tractor and implement performance real time. “Most have tons of questions. They also say nobody ever told me this.”

He explains to his visitors that farmers have to be sustainable economically and environmentally. “Cover crops and conservation tillage are meaningless if the farm isn’t economically sustainable,” he says. “I get very little push back. Most of these people are working for companies that have to be economically viable. Most of them truly gather it has to be holistically sustainable.”

He does the farming practices he does because he likes the impact on soil health and the bottom line, he says. Getting paid by an ethanol plant for producing a low-CI corn feedstock will make the practices economically sustainable for many more farmers. Participating in Gevo’s development of farm-level CI accounting, he’s learned his farming practices result in CI scores running 30 to 40 points below average, with some fields going negative.

“The question is, can we sell that product [SAF] at the end of the day that is economically viable long term,” Feikema says. “Is the consumer willing to pay for it?”

The incentives in the IRA will help bridge the cost differential between SAF and retro-jet, but DOE’s Reed acknowledges the five-year life of the incentives in the statute are not enough. “Long lifetime incentives, at least 10 years or more, will really help financing of facilities,” she says. “But also, there’s that market demand, the industry’s willingness. Are people willing to pay a little bit more?”

Creative financing packages are under consideration, she reports, where large companies could meet their sustainability commitments by paying more for SAF-fueled business travel, which would supplement the ticket price for the general population. “There are groups looking at how we can finance these technologies in a way that can take advantage of the market that’s willing to pay a little bit more until the price levels out.”

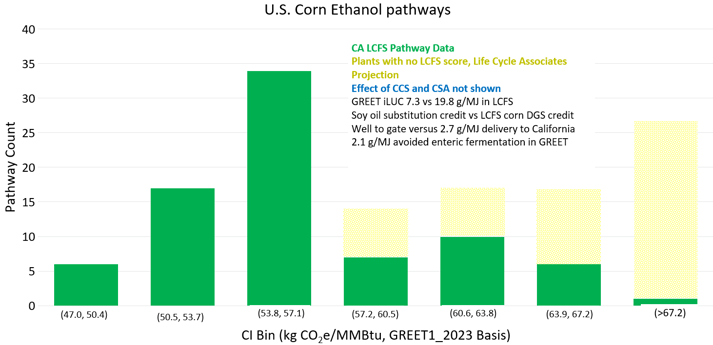

Lifecycle Associates developed the above chart illustrating the ethanol industry’s carbon intensity (CI). The green bars show the publicly available scores for plants that have applied for pathways under the California Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS). The yellow shows Lifecycle Associate’s projection of the remaining industry. California uses its own version of GREET to score its pathways, which includes higher CI for certain parameters and is roughly 15 CI points higher than Argonne National Laboratory’s GREET 2022. Plants receive LCFS scores for multiple pathways depending on things like the percentage of distillers grains (DGS) dried or wet. This chart shows the lowest score achieved. Different indirect land use change, DGS and corn oil credit, and exclusion of transport emissions account for the bulk of the difference according to Stefan Unnasch, CEO of Lifecycle Associates.

Lifecycle Associates developed the above chart illustrating the ethanol industry’s carbon intensity (CI). The green bars show the publicly available scores for plants that have applied for pathways under the California Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS). The yellow shows Lifecycle Associate’s projection of the remaining industry. California uses its own version of GREET to score its pathways, which includes higher CI for certain parameters and is roughly 15 CI points higher than Argonne National Laboratory’s GREET 2022. Plants receive LCFS scores for multiple pathways depending on things like the percentage of distillers grains (DGS) dried or wet. This chart shows the lowest score achieved. Different indirect land use change, DGS and corn oil credit, and exclusion of transport emissions account for the bulk of the difference according to Stefan Unnasch, CEO of Lifecycle Associates.